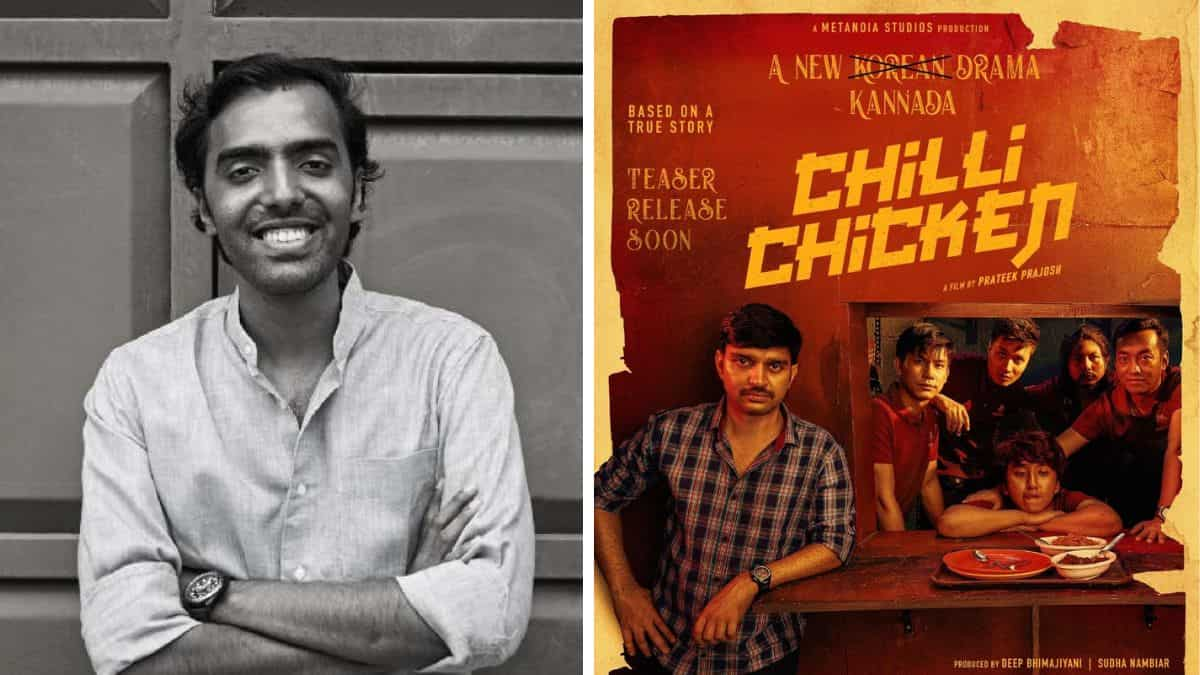

Chilli Chicken Director Prateek Prajosh On Bengaluru's Migrant Workers & Their Tryst With Kannada

8 months ago | 160 Views

For the first time ever, a Kannada film was recently released in Manipur at Kumecs cinemas and Tanthapolis in Imphal — Prateek Prajosh’s Chilli Chicken. For more than two decades, an insurgent group in the northeastern state had kept alive a call to not release any Hindi film in Manipur (some films were screened in 2023, though). However, this year, Chilli Chicken’s release was approved by the Manipur State Film Development Society. It ran for about a week in theatres there, and ironically, its box-office collections were better here than that in Karnataka.

It is beautifully ironic that a film that speaks with empathy about five migrant workers from the North East who live in Bengaluru — Ajoy (Victor Thoudam), Khaba (Bijou Thaangjam), Jimpa (Jimpa Sangpo Bhutia), Jason (Tomthin Thokchom) and Ranjoy (Hirock Sonowal)— and a wannabe restaurateur Adarsh (BV Shrunga) from small-town Karnataka got a screening space in Manipur.

The film refuses to judge anyone — it speaks about the stigma the boys face, but it also speaks of those who help by offering them a rental space in their homes. It shows some of them as stealing from their owner, but it also shows how the owner presumes he’s doing them a favour by not treating them as badly as the others treat their migrant staff.

Eventually, after many struggles and a death, everyone learns to carve out their destiny in the world of food, by working together as a unit, in the spirit of how a business should be run.

The film also shows that the workers learn Kannada, and even converse in it casually, without making a big deal of it. This part especially strikes a chord in today’s times, because the IT capital of Bengaluru is struggling to come to terms with a large group of people who say "Kannada gothilla (I don’t know Kannada)" even as they make Bengaluru their home. Things have come to a near-flashpoint now, on social media and offline.

Sadly, as is now common for non-star, non-tentpole Kannada films that don’t carpet bomb audiences with prime shows, this film too was out of theatres in its home state in a week. However, there’s hope it might find its audience on OTT soon. Because what it speaks about is universal.

In a strange way, Prateek, a commerce graduate with an MBA in media and entertainment, understands the sense of not being rooted in a place. He grew up abroad, visited India frequently, went abroad to study, dropped out, and found himself again in India.

And, while he studied something very different from what he wanted to be, Prateek found himself surrounded by film buffs — he consumed films via video cassettes and through DVDs thanks to a friendly neighbour in Oman. "Later I realised that long before I knew my interest, my destiny was being written,” he says.

Bengaluru, where he set his debut feature film, is very special to Prateek. “I have a strong affinity for the city. I graduated from Christ College and did my post-graduation at Manipal University’s Bangalore campus. I watched about six to seven films a day. However, it was my internship at LV Prasad Film and TV Academy that reintroduced me to Indian cinema, all thanks to Prof Hariharan and Prof Uma Vangal. I learnt we have a certain responsibility towards portraying gender sensitively and sensibly.”

Prateek was in Bangalore at a time when the city was in the midst of a churn. The IT industry had taken root and people from all over the country were putting down roots in Bangalore. To service their requirements, the gig economy took off in a big way. And with that came migrant blue-collar workers from across the country, especially the East and North East. The city was on the cusp of change, and with it came the attendant fissures.

Prateek’s moviemaking dream remained that. He found a life making short films and docu-features. His now-late grandmother told him about the traditional art form of Theyyam. He ended up making a documentary feature on it, and that set him on a different course. He went on to make more shorts — Rani, Pazhaya Katha Onnu, and a few in Hindi such as Piddi, Rawas and a limited web series titled What's your status. A documentary followed in Malayalam, on a national award-winning teacher Mrs Nambiar.

Prateek managed all this while working at Viacom 18 as a creative producer on films such as Manto, Padmavat, Andhadhun, Kannum Kannum Kollai Adithal and the award-winning Gujarati film Dhh.

Edited excerpts from the interview:

When did the idea of Chilli Chicken come to you?

Well, my co-writer Siddhanth Sunder gave me the idea sometime in 2014 or 2015. We began work on it in 2020. In between I had signed up to work on a couple of films, all of which got dropped, after we put in the work. That was also when I realised why you need people who produce a film to back it cent percent. A good thing that happened was that my partner and I had a baby, and I loved my role as father.

During the pandemic, I decided to revisit the script and tune it to real life, because of the stories of migrant workers I had heard, and because racism toward people from the North East peaked to an all-time high.

That your characters spoke in Kannada seems to have charmed many.

It was a very important, natural thing for the characters to do. The nature of their world makes this so much easier. If you remember, I’d ended the teaser with Jason trying to read in Kannada. I wanted to create a film about us, not them and us.

The film is clear that it treads a grey area. Everyone has their pluses and minuses.

Yes. Housing is a huge issue for workers from the North East. So, while I did write in a house owner who is willing to rent to them and backs them when neighbours protest, she also refuses to allow them to use her kitchen.

Customers think the cooks, who they call China-avru, use ajinomoto and ruin their health. Neighbour call them "chingi-pingi" and insist they will chase them to Nepal. The hotel’s clients whisper among themselves that these workers should all be taught Kannada, and are surprised when Ajoy speaks in Kannada.

Even amid the boys, there’s a clear sense of hierarchy. Ajoy knows who the boss is. The chain of command is clear. He’s secure, but the head chef Khaba is not. He’s edgy and struggles with the hierarchy.

You said you were inspired by two films for the look of the film

Yes, for visual tonality and the restaurant lighting, I was inspired by Happy Together, a 1997 Hong Kong film, and the mood of humour and sarcasm is a tribute to American Beauty.

What is your take about the bond migrant workers have with a city?

Well, they have to remain in the city, so it’s a love-hate bond. Sometimes, they learn to love the new city, imbibe local habits and go on to become better people. Sometimes, they just run with what they have.

The original ending was grim and horrifying, and my co-writer and I felt we needed to consciously move towards an open ending, because the despondency of the original ending felt like sending the wrong message.

Chilli Chicken debunks so many modern-day myths regarding food and who can play what role

Yes. Among those is that Chilli Chicken is not a staple dish in the North East! And that you can have a really mean female loan shark. Kasi (played by the lovely Padmaja Rao) was supposed to be a male character, but when we saw her in her home, we decided she’s going to play it. We did not change a single line!

The music of Chilli Chicken grows slowly on you, taking you back in time

There’s an interesting backstory. Siddharth Sundar is a theatre director too, and I used to act in his plays. He has a strong sense of musicality. We originally did not intend to have a single song, but then we found ourselves with five songs. The background score by Kaizad Gherda drew in people too.

What drew you to cinema?

My family. My dad loved Hollywood action movies, my mother loved Malayalam cinema and my grandmother loved Tamil cinema, and they all shared stories about the films they loved. And so, a boy originally from Kerala, and brought up across Qatar, Oman and Dubai, and who spent summer holidays in Bangalore in Karnataka and near Kannur in Kerala, grew up an avid watcher of cinema, in village single screeners and huge halls in metro cities.

Did you consciously leave the place of origin of the migrant workers vague?

Not really. I wanted to avoid stereotyping. Bijou Thaangjam who plays Khaba is a Masterchef contestant. In the film, Ajoy, Khaba and Jason are from Manipur, Jimpa is from Tibet. We wanted them to stick to their roots, because it is an extension of who they are.

How does the film resonate now in the current climate of language supremacy and the call for those from outside to learn Kannada?

Within the world of this film, we see the boys speak Kannada, albeit broken and not with the fluency you’d expect from a native speaker. They learn to speak it because of their need to survive in a new city, and it’s also what their job demands.

Personally, I feel that rather than force, sensitising people toward cultural nuances may be a better approach. It’s still okay if you don’t know the language, but you better not joke about it and appear dismissive towards it.

Read Also: Love Insurance Kompany: Krithi Shetty’s poster is quirky, girly and fun

#