Rude Food by Vir Sanghvi: State hero, national champ

9 months ago | 89 Views

What do Indians like to eat when we go out for a meal? If you answered ‘pan-Asian’ or ‘pasta’ or ‘south Indian’ or even ‘modern Indian’, well, thanks for that thought.

But you are utterly and completely wrong.

As much as things may have changed in recent years, the top two eating-out cuisines in India are still Punjabi and Punjabi. Or, more correctly, while they are not necessarily the food that Punjabis eat at home, they are still restaurant cuisines created and popularised by Punjabis.

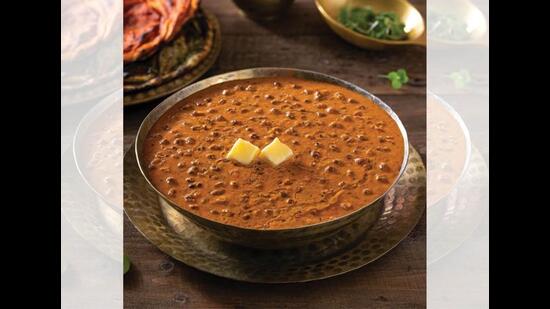

The first is the butter chicken-dal makhni kind of staple restaurant food served all over India. The second is Punjabi-Chinese or Sino-Ludhianvi, invented by Punjabi restaurateurs in the 1970s and 1980s.

Enough has been said about Indian Chinese (mostly by me!) but we tend to take Punjabi restaurant cuisine for granted, never recognising quite how ubiquitous it is all over India. Over a decade ago, I went to shoot at a resort in Kerala. As most of the other guests were locals, I looked forward to some good Malayali food. In fact, the hotel had a buffet every day, with such dishes as paneer makhni and tandoori vegetables. When I remonstrated with the chef, he quickly set me right. “Look”, he said. “You come from outside. But most of my guests are from Kerala. They eat Kerala food at home every day. When they come out, they want to eat butter chicken. And that’s what I give them.”

The chef was right, of course. A recent survey by the National Restaurant Association revealed that 63 per cent of all Indians want to eat North Indian food when they go out. When you look through the lists of the most-ordered dishes on delivery apps, North Indian beats every other kind of Indian cuisine. Even the biryani that is the most popular dish is usually a long-grained rice biryani made in the North-Indian style.

The rise of Punjabi food can be traced back to the Second World War and Partition. Many of the earliest restaurants in Delhi’s Connaught Place opened to cater to US and British soldiers. After the war ended, the restaurants found they had to Indianise their offerings to suit the new, mostly Indian, market.

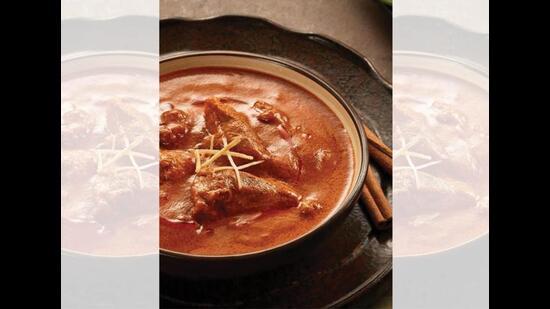

Many of the owners of these restaurants (as well as many restaurants in Mumbai and Kolkata) were Punjabis and the food they served was a heavily bastardised version of the food they ate at home, plus versions of biryani and rogan josh that their cooks made for them.

A second Punjabi push came in the 1950s, when many of those who had come over after Partition with very little, began opening small restaurants to make a living. The Moti Mahal story is well known and the influence of that restaurant’s food — tandoori chicken, butter chicken and dal makhni — was phenomenal. Soon, even existing restaurants began installing tandoors and altering their menus to take into account the new dishes that were created by Moti Mahal.

That trend has persisted to the present day. We may have more choices now apart from Kwality, Volga, Gaylord and the other familiar 20th Century names, but no matter what the restaurant is called, the menu is still roughly the same.

I always remember my late friend, Jiggs Kalra, who did so much to popularise the cooking of Lucknow and other cities. But Jiggs told me he never doubted that, at the end of the day, the eating-out market was mostly Punjabi. In 2008, Jiggs started food counters under the name of Punjab Grill, which he ran with his son Zorawar. The menu was solidly Punjabi (as the name implies) but he tweaked the spicing and the marinades to give the food a distinctive taste.

Jiggs was a great foodie, but not keen on the business part of restaurants so he went into a partnership with Lite Bite Foods, a company owned by Amit Burman and Rohit Aggarwal. Using Lite Bite’s capital, new full-service Punjab Grill restaurants opened in Gurgaon and Delhi to an excellent response. In March 2012, Lite Bite brought out the Kalras for a large sum, which Zorawar used to launch his own (now flourishing) empire, including brands like Made In Punjab, dedicated to the same sort of philosophy. I use Punjab Grill as an example because of its size and success but there are many other Punjabi restaurants all over India, serving roughly the same sort of food.

You would think that because Punjab Grill started in 2008—and many standalone Punjabi restaurants are over 50 years old —it would face turbulence in the decade and a half that followed. But no, the chain has continued to grow. It now has 52 branches all over India, all full-service and all operated by Lite Bite. (There are no franchisee-run restaurants.) Punjab Grill is present in 17 cities, has ambitious growth plans and will reach 100 restaurants in a couple of years as its aggressive expansion continues. (There are also five Punjab Grills abroad.) Nobody in the restaurant business likes providing figures, but Lite Bite says that it aims to make Punjab Grill a ₹700-crore brand in the next five years or so. (Industry estimates say that the brand is worth about ₹250 to Rs300 crore at present. The company will not comment.)

How did Jiggs’s original idea end up becoming one of the largest (or perhaps the single largest) North Indian chain of full-service restaurants in India?

I checked out the menu to see how the concept had evolved over the last decades.

What I found surprised me: It’s more or less exactly the same menu as the one they had when I first dined out at a Punjab Grill in the Jiggs era.

There are the familiar tweaks. Tandoori chicken is called Bhatti da Murgh. The Dal Makhni is called Dal Punjab Grill. But otherwise, if you read the menu, nothing would surprise you very much: Butter chicken, Sikandari raan, chicken seekh kababs, tandoori gucchi etc. By and large, they have kept Jiggs’s recipes.

In that sense, the story is the same as Bukhara, not just the most famous Punjabi restaurant in the world but also India’s number one restaurant. Bukhara’s menu has not changed since it opened in 1978. Punjab Grill has taken the same “if it ain’t broke, why fix it?” approach.

It now serves essentially the same menu at all 52 of its restaurants in India. I asked Rohit Agarwal if they intended to innovate and be different. No, he said. They were very happy with the menu that they had served since the beginning.

I always think that the success of places like Punjab Grill, and the thousands of standalone Punjabi restaurants and the lakhs of happy customers they feed every day, to say nothing of the crores they make, all serve as a lesson to those of us who call ourselves foodies. We are happy to celebrate super-high quality (Bukhara) or innovation (Indian Accent) or to write about street food, dhabhas and home chefs. But what we forget is that as interesting as these sectors are, they are not the heart of the restaurant business.

Punjab Grill (and restaurants like it) succeed because the food is comforting and familiar. The quality is consistent. (There are many behind-the-scenes systems and training programmes to ensure this.) Alcohol is not a large part of the offering; some restaurants don’t even serve liquor.

The emphasis is two-fold. At lunch, the restaurants must serve as relatively upmarket places where a corporate executive can take a client. And at dinner they should be seen as safe, family-friendly places. Nobody goes there for gastronomic innovations or celebrity chefs. And though some branches (like the one in Delhi’s Aerocity) look upmarket enough to be restaurants in five-star hotels, there is no great emphasis on creating a luxury ambience.

Since Jiggs opened the first Punjab Grill in 2008, there has been at least one generational change in the demographics of the customers. But it has made no difference. In fact, the restaurants do better and better: New generations are as happy with dal makhni and tandoori chicken as their grandfathers were.

I don’t think it will change. Of course Indian gastronomy will evolve. But at its heart will always be Punjabi restaurant food and Punjabi restaurants. Our grand children will, no doubt, be ordering butter chicken and dal makhni long after the dishes invented by modern Indian chefs are forgotten.

India will change. But the tandoori chicken will remain our national bird.

Read Also: what is hematuria? causes, early signs, prevention tips to know

#