Arcs de Triomphe: Here are the most evocative tales from India at the Olympics

2 months ago | 25 Views

What is it that we love about the Olympics? Is it the thrill of seeing fellow humans do the seemingly impossible? Is it knowing what they have endured to get there?

Either way, we are in luck. Another Olympics is upon us. Since the pandemic pushed the previous one in Tokyo by a year, we have the Paris Games seemingly arriving sooner. Hopes and anticipated medal counts are being debated and we will have our fill of predictions soon enough.

Today, we deviate from the norm to look at eight athletes picked for their journeys and stories, over their prospects (although we are rooting for them): Sharath Kamal, Dhinidhi Desinghu, Vinesh Phogat, Sandeep Singh, Nikhat Zareen, Harmanpreet Singh, Tulika Maan and Jyothi Yarraji.

Sharath made his first Olympic appearance at Athens 2004, a year before Rafael Nadal won his first Grand Slam. The elder statesman of the Indian table tennis group, he is the person typically helping coordinate a sparring camp in Europe for national players at short notice, or sitting down with coach Massimo Costantini to go over the details at camp, when everyone else is taking a beat. The Olympics have been a bridge too far for Indian table tennis, for far too long. At 42, Sharath’s limbs and hips have endured enough, but he doesn’t want to give up without another go at his dream. There’s gas in the tank for one final stab, he says.

At the absolute other end of the age range is Desinghu, a Class 9 student, a swimmer, and the youngest member of the Indian contingent. The 14-year-old will arrive in Paris wide-eyed, looking to catch a glimpse of her idol Katie Ledecky, and going as fast as she can in the pool.

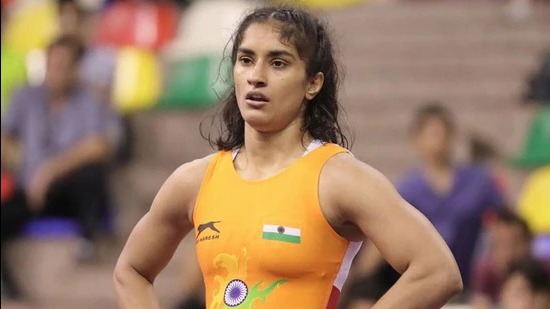

Few Olympic-bound athletes have perhaps endured what Phogat, 29, has over the past year. She was at the forefront of public protests against former Wrestling Federation of India (WFI) chief Brij Bhushan Singh, who is accused of sexually harassing female wrestlers. While athletes around the world were training for Paris, she and many of her fellow wrestlers were being roughed up, yanked off the streets and stuffed into police vans. A medal in Paris will be redemption for India’s most decorated Indian female wrestler, on many counts.

For Sandeep Singh, 28, redemption is probably defined as being able to give his family a better life. Growing up, he accompanied his father, a labourer, to construction sites for masonry work. Joining the army was a way out of poverty. He became a rifleman, and was once posted at the inhospitable Siachen Glacier. He has now pulled off a shocker, upstaging former world champion Rudrankksh Patil in the qualifying trials, to make the Olympic team.

In the past, Zareen has had to make way for India’s most celebrated boxer, Mary Kom, since they belonged to the same weight class. She announced her arrival in a new weight category last year, with a World Championship gold. The best Indian boxer headed to Paris, Zareen, 28, has waited her turn to get here.

Wait and Indian men’s hockey go back a long way. Captain Harmanpreet Singh, 28, has seen the abyss of Rio 2016 and the 41-year wait-ending medal in Tokyo. India’s go-to man in penalty corners, he will want to go all-in for a successive medal.

If ippon (a move/throw that awards an automatic win) makes it to the glossary of terms you discover at this Olympics, you might have Tulika Maan to thank. The lone Indian judoka in Paris this summer, the 25-year-old was raised by a single mother. She took up judo as a child. It was a healthier option than staying home alone after school or whiling away afternoons at the police station, where her mother was a cop. Two years ago, Maan won silver at the Commonwealth Games. She is now headed to her first Olympics.

On the subject of resilient mothers raising remarkable athletes, we have Yarraji, 24. The current national-record-holder in the event, she will be the first Indian woman to compete in the 100m hurdles at the Olympics. She has had a tough childhood and watched her mother work two jobs, as domestic help and a hospital cleaner, to be able to put food on the table. The hurdles on the track might not seem as daunting.

REMARKABLE TALES FROM INDIA AT THE OLYMPICS

At 42, his last run

The first time Sharath Kamal found himself in an Olympics dining hall, he had to pick his jaw up off the floor. It was Athens 2004. He was part of the table tennis squad, and sharing a table with tennis star Roger Federer.

He was too awestruck to keep his eyes on his plate. “I thought, ‘Wow, my Olympics are done, I can go home now’,” Sharath says, laughing.

Two decades on, he is headed to his fifth and final Games. The 42-year-old jokes that his wife is likely to abandon him if he decides to soldier on any further.

He will be the flagbearer for the Indian contingent, alongside badminton star PV Sindhu.

Tokyo was supposed to be his last Olympics. He ended up taking a game off the legendary Ma Long in the third round. With the gap between the postponed Tokyo and the Paris Games cut short by a year, and his body holding up, the 10-time national champion and Asian Games and Commonwealth Games medallist grew hungry for a final shot.

In March, he had his best-ever showing at a World Table Tennis event, making a run to the quarterfinals in the Singapore Smash.

History was made when both the Indian men’s and women’s teams qualified for the team events in Paris. India has never medalled in table tennis at the Olympics.

“After the 2022 Commonwealth Games, I decided to make the team event my focus for Paris,” says Sharath, ranked 40 in the world. “We ended up qualifying. If that hadn’t happened, I don’t know what I would have done. But here I am headed to my fifth Olympics. My body feels good for my age, and I know I’ve put in the work in training. Who knows what might happen?”

At 14, India’s youngest

Even for elite athletes, the Olympics are a lifelong dream, a pinnacle they hope to reach at least once. Dhinidhi Desinghu is already here, at 14.

The swimmer from Bengaluru is the youngest person in the Indian contingent. She will compete in the 200m freestyle event after receiving one of two Universality quota slots (no Indian swimmer made the cut in direct qualification).

“This was one of my biggest dreams, and to get there at this age is amazing. I’m glad that the hard work and effort I put in paid off,” she says. “This is just the beginning of my journey. I just want to experience the Olympic stage this time.”

Veteran swimming coach Nihar Ameen, at whose academy Desinghu trains, reckons she is the best Indian woman swimmer today. At last year’s senior national championships, Desinghu, then 13, won the 200m freestyle gold, which earned her a spot at the Hangzhou Asian Games last year and at this year’s Doha World Aquatics Championships.

Pitted against world-class swimmers, the room for improvement was evident. But for someone who only started swimming six years ago, it’s a remarkable story.

The Class 9 student wants to use this Olympic opportunity “to see what I can do in a different environment”. And to see one of her idols, US seven-time Olympic gold medallist Katie Ledecky, up close. Desinghu has made handwritten gift cards for the American, and hopes to hand them over in person.

A soldier, a wild-card entry

Going into the domestic trials, air rifle shooter Sandeep Singh was a rank outsider. Few outside the circuit had heard of him, and he was up against some serious heavyweights, including 2022 World Champion Rudrankksh Patil and Tokyo Olympian Divyansh Singh Panwar. Singh chose this moment to spring a surprise and top the trials.

He is now headed to Paris. It’s an unlikely outcome for a range of reasons.

Born in Behbal Khurd village in Punjab, Singh grew up accompanying his father, Baljinder Singh, to construction sites, to help earn money for the family. His father was a day labourer, his elder brother a motorcycle mechanic.

“I have done everything, from lifting bricks at a construction site to masonry. The dream of an Army job kept me going,” he says.

The Army dream came true, bringing with it a different kind of hardship and strain. His sense of singular focus was forged in one of India’s most inhospitable terrains, the Siachen Glacier.

The 28-year-old speaks of sport as a luxury, and viewed through his sights, one can see why. There will be no real threats on the shooting range; the fight for medals will be intense but benign.

His real challenge now is to cross that vital line from good to great. Who knows… he might just spring another surprise.

Finally, the ring she wanted

Until boxing legend MC Mary Kom ended her stellar career at the Tokyo Games, Nikhat Zareen remained in her shadow, waiting for the opportunity to represent India at the Olympics. Now it is here, and the 28-year-old is prepped and ready.

For two years, she has been on fire, winning back-to-back world championship titles, the Commonwealth Games gold and the Asian Games bronze in the flyweight division (50-52kg). She will enter the ring knowing she is expected to medal. Her country expects it, and it has been her lifelong dream.

It’s a dream that took shape in the bylanes of Nizamabad in Telangana, and became an obsession as she rose in stature. Growing up in a middle-class home — her father Mohammad Jameel Ahmad is a sales officer and her mother Parveen Sultana, a homemaker — she saw boys train in boxing but not girls, and decided to change that.

With a now-familiar mix of grit and tenacity, she took great pride in boxing with the boys (unavoidable, since there were no girls to box with). Her big break came in 2011, when she won the junior world championship. Fierce and unforgiving in the ring, she has waited restlessly for a chance to step forward.

By 2019, she couldn’t wait quietly any more. She demanded a chance to take on Mary Kom, ahead of the Tokyo Olympics. “All I want is a fight in the ring,” she said.

She got her face-off, and lost to Mary Kom. She was disappointed, she said then, but she knew her time would come. Perhaps that time is now.

Channelling deep emotion

Tulika Maan was raised by a single mother, Delhi police officer Amrita Singh. Her father, Satbir Maan, was murdered over a business rivalry when she was two.

As a child, Maan was lonely, angry, confused. She spent numerous afternoons at the Rajouri Garden police station while her mother was on duty. Or she spent her afternoons alone at home. She began to seek comfort in food, and gained an unhealthy amount of weight. This is when her mother signed her up for a judo class.

The combat sport changed everything. Maan was soon pouring all her energy into it and winning medals at school, then at the state level, then at junior meets. In judo, she has said, she found a way to process her feelings. She found a sense of purpose.

A six-time national champion, she won silver at the Birmingham Commonwealth Games (+78kg) in 2022. Now, the 25-year-old is India’s only judoka at the Olympics.

Her 6-ft frame holds hope, ambition and power. On her best day, she can challenge the best.

So many firsts

With a trace of pride in her voice, Jyothi Yarraji says there is no girl from her family, “close or extended”, to have “gone out and done things like this”.

By “this”, she means the hurdles, on the track, and on her road to becoming India’s top hurdler and national 100m record holder.

Yarraji, 24, is also now the first Indian woman to compete in the 100m hurdles at the Olympics, having qualified for Paris on the basis of her world ranking of 24.

Born in Visakhapatnam, she grew up poor. Her father worked with a private security company; her mother worked as a domestic help.

Yarraji dreamed of being “successful”, and she soon realised athletics could be her best shot at this. She famously got her start after being spotted by Sports Authority of India (SAI) coach N Ramesh in 2014, at age 14, during selection trials in Hyderabad. She had turned up “with no particular event in mind”.

Another major turning point has been her time at the Reliance Foundation’s Athletics High Performance Centre in Odisha, which she turned to after coming off a long injury layoff, in 2021. She arrived there low on self-belief. But since then, British coach James Hillier, the foundation’s athletics director, has gradually worked to get her back on her feet.

She is now sailing over the hurdles again.

In 2022, Yarraji broke Anuradha Biswal’s long-standing national record, at a meet in Cyprus. She has re-set the national record several times since.

In between, she stood up to fight for her rights at last year’s Asian Games final in Hangzhou, after being disqualified alongside China’s Wu Yanni, over a misjudged false start. The Indian would eventually walk away with silver, another glittering milestone on a road full of promise.

Coincidence births an icon

It was pure accident that led Harmanpreet Singh to hockey.

He had always been athletic, playing football and volleyball and competing in track and field events at his school in Jandiala Guru, Punjab.

“Since we were interested in sports, my friends and I decided to go to a local academy during our summer vacation, when we were 12, to pick up a new sport. The only trainer we found there was a hockey coach, who asked us to try it. That is how this beautiful journey started,” says the India skipper.

It soon became clear that he could excel in this field and so, at 12, he moved to the residential Malwa Hockey Academy in Ludhiana. He then joined the renowned Surjit Singh Hockey Academy in Jalandhar, which has produced several India players.

He made his debut for India at 19, in 2015. He was on the squad that went to the Rio Olympics in 2016 and suffered heartbreak there, as India were knocked out in the quarter-finals.

The tide turned five years later, at the Tokyo Games, when Singh, now one of the best penalty corner (PC) specialists in the world, emerged as India’s highest scorer, with six goals that yielded the country’s first Olympic hockey medal in 41 years, a bronze.

In Paris, Singh, now 28, will be India’s primary weapon in PCs and the back line. As captain, he is eager for the team to medal up at these Games.

Any medal at all will be India’s first successive win in Olympic hockey, in 52 years.

A warrior returns

The poster girl for Indian wrestling heads to her third Games to realise a long-standing dream: that of winning an Olympic medal.

After earning her spot at a domestic qualifying event in March, the 29-year-old said, “I am not finished yet. The dream is alive and so am I.”

In Paris, Vinesh Phogat will have to summon every ounce of her strength to stand a chance, in one of the toughest weight divisions (50kg) in women’s wrestling.

The two-time World Championships bronze medallist is coming off a tough year, one that has seen her wage a punishing battle against former Wrestling Federation of India (WFI) chief Brij Bhushan Singh. The exhausting fight, she says, has been the toughest bout of her career.

Phogat has missed trainings and competitions, but has warmed up for Paris by winning the Grand Prix of Spain this month. She is ready, she says.

An Olympic medal has so far eluded her. Phogat failed to get past the quarter-finals in her two previous attempts.

A medal in Paris would be a fairytale ending.

#