Hold on to your hearts: The rise of the de-influencer

4 months ago | 53 Views

It can be hard being a naysayer on Instagram, where one must be happy, positive and peddling in order to make it.

But the harder it becomes to say “Stop… is that even true”, the more essential it is to do it.

That is what drives embryologist Dr Tanaya Narendra aka @dr_cuterus, 30. Her mission is to keep people from using products that cannot help them, and could actually harm. “It’s horrifying when a 14-year-old writes to me saying they have chemical burns after bleaching their genitals,” says the doctor from Allahabad with 1.8 million followers.

Revant Himatsingka’s mission is simpler, but somehow more controversial. On his popular account, @Foodpharmer, which has a following of 2.7 million, the 32-year-old simply reads out food labels and explains what they mean.

Somehow this has turned him into a hero to some (“I get stopped in the street and asked for selfies”) and a villain to others (a common question from fans is “How many cases currently?” The answer right now is six).

The first case scared him. Then lawyers showed up to tell him what he already knew: he had done nothing wrong. And fear turned to anger. “Why shouldn’t I be able to talk about what’s on food labels?” he says. So this is now the purpose of his account.

In a world of influencers peddling commercial content disguised as personal experience and opinion, it is a financial non-starter to do the opposite and shout out the very things that companies do not want broadcast. And so “de-influencers” such as Himatsingka and Dr Narendra don’t expect to earn any real money from their accounts.

He speaks at corporate events to keep going. She has her clinic and her patients, and occasional projects with the union government and World Health Organization (WHO).

Even travel content creator Aakanksha Monga can see the difference in the number of views she gets — for posts that discuss what a place is really like — and the far higher numbers of views for cookie-cutter, faux-picturesque Reels about “top 10 things to do”.

She has 1.1 million followers, though, and she believes these are travellers who want to make informed choices.

Promoting mindful choices is what drives Soumya Manthena of @greenfeetcleanfeet. Her account explores “make-don’t-buy” recipes for things ranging from cleaning liquids to protein supplements. She also explores why popular hashtags (#GoGreen; #ClosetCleanse) can do more harm than good.

“There is something for everyone to do. But the right kind of change involves understanding the trade-offs involved,” Manthena says. “There is no need to blindly shift from a plastic comb to a wooden one that may break faster, or throw out a perfectly good polyester outfit just to hoard new handloom sarees.”

Instead, she says, look within before ordering online: What do you have in your closet, kitchen cabinet or storeroom that could be modified, repurposed or reused?

This kind of thing could open up new battlefronts for brands, says Michael Serazio, journalist, communications professor at Boston College and author of The Authenticity Industries: Keeping It “Real” in Media, Culture, and Politics (2023). “Authenticity is a kind of quasi-religion now, across many domains of media and culture. When social media is saturated with promotional content, de-influencing becomes a way of standing out ‘authentically’.”

If de-influencers — currently a small but growing group around the world — can stay the course and multiply, “it could be a public-relations crisis for certain brands,” adds Kristen Ruby, a New-York based social-media analyst, TV commentator and head of an eponymous PR agency. Watch out for the mission itself being hijacked, Serazio says, with fake de-influencers being paid by one corporation to criticise another.

What does it take to stay authentic, in an increasingly inauthentic realm? Meet our pick of India’s top de-influencers today.

.

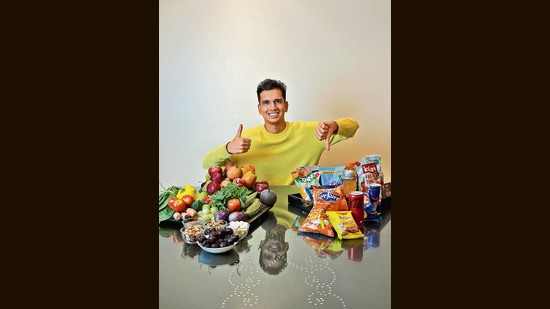

Beyond buzzwords: Reading food labels

Revant Himatsingka, 32, doesn’t see what all the fuss is about.

He analyses food labels online, and is hailed as something of a hero for it. People stop him in the street and ask for selfies. A common question, gleefully asked, is how many cases he currently faces (the answer is six).

“I like to think of my work as a review,” he says. “If I don’t like a movie I’ve watched, I can easily talk about why I disliked it, and no one would file lawsuits. So why can’t I just read the label of a food product and tell people what I see?”

Himatsingka, who has an MBA from Wharton School, has built up a following of 2.7 million on Instagram (@Foodpharmer), in just over a year, doing this.

His explainer Reels focus on nutrition literacy, pointing out, for instance, that if one reads a certain label carefully one can see that there is more sugar than tomato paste in that brand of ketchup, and no hazelnuts at all in a certain “chocolate-hazelnut” spread.

He lays out guidelines for how to distinguish between healthy and healthy-sounding tags (“multigrain bread may still have maida or refined wheat flour as its main ingredient,” he says).

Himatsingka first became wary of packaged foods while living in the land of bad food choices, the US, where he spent 13 years studying and then working as a management consultant. While there, he also wrote a self-help book titled Selfienomics (2016). Then, in the pandemic, he quit his job and returned home to Kolkata (he now lives in Mumbai).

He had about 1,000 followers when he began posting regularly, in 2023, to promote his book. It contained a chapter about food labels, so he created a video about the sugar content in Bournvita (which was then 50 gm per 100 gm; it has since been reduced by 15%).

The post went viral, and he was served his first legal notice, by the brand’s owner Mondelez.

“The next few days were pure panic,” he recalls. “I was confused. My family was scared. We were talking to lawyers all the time. Far-flung relatives would call to tell me that life as an ‘activist’ would only lead to jail time.”

His follower count shot up to 100,000 in nine days. Then lawyers turned up in his feed, offering pro-bono representation. The think tank Nutrition Advocacy in Public Interest India (NAPi) spoke up in his support. He went from being afraid to being angry.

Why shouldn’t he be able to talk about what was on food labels? He decided this would be the purpose of his account.

“I intentionally read only what’s on the packaging, to show how several top brands routinely contradict themselves,” he says. “I don’t ever say things like ‘Sugar is poison’ or ‘Do not eat this’. I just think people should know what they are choosing.”

Since no one is ever likely to pay him for his posts, he has found other ways to earn from his work. His primary revenue stream at the moment is speaking at corporate events.

There’s still a long way to go, he says. When people run into him in public, for instance, they often ask: Is xyz brand safe? And he has to explain the difference between “safe” and “healthy”.

“Sometimes I also wish people would ask me about my life outside food labels,” he adds, laughing. “I do have more on my mind than the amount of sugar in a glass of cola.”

.

What bras, lotions and steam can and cannot do

As an embryologist who routinely consults with couples struggling to have a child, Dr Tanaya Narendra, 30, answers strange questions for a living.

“Could eating a banana daily help me guarantee a son?” “Could the delay be because I am not manly enough?” (The answers, of course, are why; and of course not.)

As @dr_cuterus on Instagram, she has gathered a following of 1.8 million with her simple truth-telling and myth-busting. She receives messages that range from the heartbreaking (“My husband thinks my body is abnormal”) to the absurd (“Can I make my face brighter by massaging it with semen?”).

Her mission, lately — amid a new wave of products aimed at women’s “hygiene” — is keeping the uninformed safe. “It’s horrifying when a 14-year-old writes to me saying they have chemical burns after bleaching their genitals,” says the doctor from Allahabad.

And so she breaks down how bras cannot change the shape of a woman’s breasts; why creams cannot alter their size; and why chemical-laden “vaginal cleansers” are not doctor-recommended. She does it all with tact, empathy and humour. (“Your vagina is not a momo; it does not need steaming.”)

She has received one legal notice so far; the case has since been dropped. She often gets DMs from company representatives threatening to sue, but no one else has.

Meanwhile, she expanded her Instagram operation in 2022 and now has a team of three helping her with her content. “These are people with different backgrounds and sexual orientations, so they can help me create content that’s inclusive and can change the kind of healthcare I provide,” she says.

She has worked on projects with India’s union ministry of health and family welfare, and the World Health Organization (WHO), and is determined to use these and other non-commercial means to keep her work on Instagram going.

“It makes me very angry that the misinformation crisis is getting harder to fight,” she says. But that only means it’s more important to keep fighting.

.

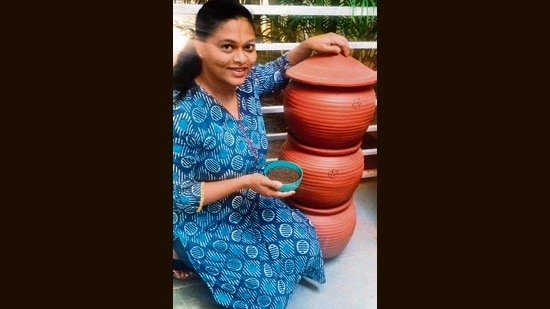

Waste not: Home is where the mart is

It was a sense of loneliness that prompted computer engineer-turned-homemaker Soumya Manthena, 39, to set up an Instagram account about sustainable living, in 2019.

“I felt like I was the only one carrying my steel bottle around. It was becoming hard to stay motivated,” she says. “I started out just looking for community.”

She found it, and a lot more. As she posted about her experiments with things like homemade bio-enzyme cleaners, she was surprised to see engagement climb. People wrote in with questions, shared hacks and stories of their own hits and misses.

She was soon segueing into other subjects she felt passionately about: waste audits, greenwashing, the ills of fast fashion.

Today, her handle @greenfeetcleanfeet has over 27,000 followers. Her posts and videos promote small, slow, mindful lifestyle changes that could include shopping at the local kirana store to reduce the use of packaging, learning about which fabrics last longest, or making one’s own protein supplements.

She explains why a “sudden closet cleanse” can do more harm than good. “There’s no need to blindly shift from a plastic comb to a wooden one that may break faster, or throw out a perfectly good polyester outfit just to hoard new handloom saris. The right kind of switch involves understanding the trade-offs involved.”

With a view to helping people understand the trade-offs, Manthena walks her followers through No Buy Challenges, Book Swaps and Waste Audits, using examples from her own life in Hyderabad.

She turns down all offers from brands because the idea is to discourage consumption and remind people to look within, in the closet, kitchen cabinet, storeroom, for things that can be reused or repurposed instead.

One of the things to consume less of, she points out, is social media itself. She recently took a break that ends next week, to get away from the “dread of eco-anxiety that creeps in when one is so involved”, and recalibrate.

It can get stressful online, she says. “There will always be people who find fault with what you do. Don’t let them keep you from living a better life.”

.

Wander woman: The truth about travel

When Aakanksha Monga was planning her trip to the Nubra Valley in Ladakh three years ago, she couldn’t wait to see the picturesque dunes and double-humped Bactrian camel described by so many travel vloggers on Instagram.

What she saw instead shook her. “The desert I saw was filthy, with trash strewn everywhere,” she says. “The camels looked scrawny and tired.”

It made her think about how travel-related content often misrepresents the experience, deliberately leaving out the uncomfortable details.

Fresh out of college and working remotely with a management consultancy, she began to travel more herself, to Himachal Pradesh, Goa, the Andaman Islands. She began posting tips and impressions on Instagram in response to questions from friends and colleagues.

As she talked about which places were over-hyped, what she really appreciated about a destination, and secret haunts and quieter getaways, she saw her follower count climb, from about 20,000 in 2021 to 1.1 million today.

Monga, 25, has since quit her job and is now a full-time content creator. In some of her videos, she busts myths about travel in general, discussing aspects such as travel burnout and the legitimate fear of falling ill while far from home.

It’s the opposite of what most brands who approach her want her to do. Her videos don’t get the reach of Reels that list “top ten” things to do. “I feel a sense of responsibility, knowing that my job has both positive and negative impacts on a place,” she says. “But I think people should make informed choices.”

In a world of AI-generated content and filters on everything, she adds, she can also sleep at night — wherever in the world she is — knowing that she didn’t lie to her audience.

Read Also: European Roma Holocaust Remembrance Day: A personal account

.webp)